Security incidents and bomb threats in schools – is your school’s plan effective?

10 July 2024

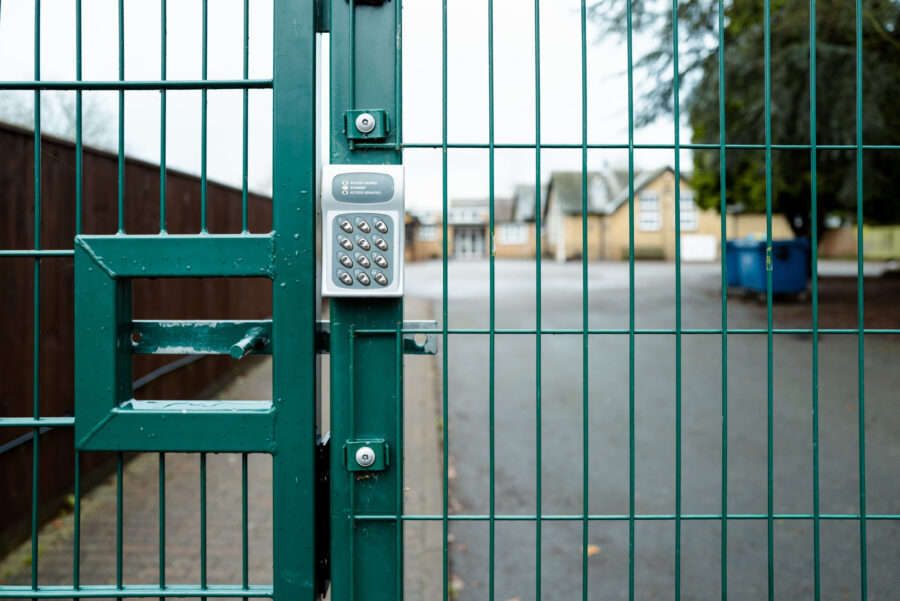

The Department for Education has published non-statutory guidance “Protective security and preparedness for education settings”, aimed at helping educational settings to become better prepared for and able to respond to terrorism and other major incidents.

Staff roles

Pursuant to the guidance, schools should appoint an individual to lead in health and safety and security, being either be a teacher, headteacher or a designated security lead. The security lead will have responsibility for co-ordinating and overseeing the school’s preparedness for security incidents. Specifically, they are expected to:

- Develop and maintain security policies and plans

- Determine how staff should respond to different types of incidents, ensuring they know their roles and responsibilities and are appropriately trained

- Liaise with external agencies, including police and emergency services, forging effective communication and collaboration

- Manage and delegate the response to an incident, with deputies who are able to act appropriately in the absence of the security lead.

A separate incident lead role should also be appointed to take responsibility for responding to an active incident. This would include:

- Leading the initial response to the incident with prompt decision-making to get people to safety

- Responding to safety concerns, such as people who have been reported missing

- Communicating with parents of those affected

- Leading on social media and mainstream media communications where necessary.

Is it appropriate to hold practice security drills?

Whilst practice drills are an important tool to understand the effectiveness of the school’s security and incident planning and staff responsiveness, schools should be careful to consider how to conduct drills, and whether to involve pupils.

Generally, primary school and early years learners should not be involved in a security drill, which should be held when learners are not on the site. However, pupils of secondary school age and older may be involved in security drills as a means of sharing security awareness and the school’s incident response plans.

Whilst the aim of a drill is to try to create realistic scenarios, it is important not shock or frighten pupils. This means that, in accordance with the guidance, drills should not mimic behaviours of: someone intending to cause harm, such as shouting, running, or waving weapons, crying or panicking, or mimicking police officers.

In addition, some pupils may have experienced traumatic situations, and it will be important to provide appropriate emotional support to these pupils. This could include giving prior warning of any safety drill and giving them the choice to opt out. It may also be appropriate to have a member of staff stay with them during the drill.

In reality, a security incident may not be restricted to just one school site, and schools may therefore need to test and practice alerting nearby schools of the incident taking place. The guidance recommends involving nearby settings in security drills where possible. It also recommends considering whether to involve your governing body, the local authority, or the local police, to either take part in the drill, or support an evaluation.

How should suspicious activity be managed?

The guidance provides advice for staff in identifying suspicious activity. This includes someone trying to remain hidden, take photographs, or asking unusual questions, and responding to an unattended or suspicious item including ensuring clear communication throughout the school, and ensuring a culture of general tidiness to help to identify anything suspicious.

Bomb threats

As well as broader security risks to school, the guidance sets out the expected response to a bomb threat at school.

In terms of the school’s response, the guidance sets out key points for schools to consider when responding to a bomb threat. For example, where a threat is made by telephone or in person, an appropriate member of staff should try to gather more information from the individual by keeping them talking.

Helpful information to try to harness includes when the speaker plans for the bomb to go off, their motives, and contextual indications such as whether the individual has an accent, their gender, background noises, and the phone number which they are calling from.

Schools should also have in place a ‘bomb threat checklist’ setting out the steps to be taken, and details to record, in the event of a bomb threat. The police should be phoned as soon as possible, and the security lead or another senior member of staff should be notified as soon as possible. Whilst the police will provide advice, the incident lead should consider:

- The safest exit or evacuation routes

- Whether anything has happened previously which may be linked to the bomb threat, including whether there is a chance it could be a last day of term prank and the credibility of the threat

- Checking recent CCTV footage if safe to do so, as it may provide additional useful information.

What are the incident response options?

Pre-planned response options are set out in the guidance. These include putting the school into lockdown by barricading doors and windows, turning off lights and closing blinds, and identifying spaces in rooms where people can hide. Schools should be conscious that younger children or those with special educational needs may be fearful of dark rooms, and in such cases incident response plans may instead require lights to be dimmed and ear defenders to be provided to help children to remain quiet.

Practical steps

Preparing a robust plan is the first step in ensuring that your school is prepared for any incident. In some cases, it may be that your security plans can be incorporated into an existing policy, or will need to be prepared as new plans. Whichever option is chosen, consulting members of staff and the governing body can help to ensure that your school’s plan is robust.

The guidance confirms that school security and preparedness plans should cover:

- The context and purpose of the policy

- Leadership, accountability and assurance

- Staff roles and training

- Grab kits

- Communicating during an incident

- Response options.

Editable templates, including a “protective security and preparedness self-assessment”, have been provided for use by schools to support good practice and ensure that it becomes embedded in school procedures.

Regular testing of security plans can help to ensure that they are suitable and effective and identify any staff training needs.